Chicago:City of Innovation

Before Chicago became the bustling metropolis that it is today, it had to start small. Originally known as Chigagaou, which roughly translates “The Wild Garlic Place” in the Miami Native American dialect, the land went uninhabited by local Native American tribes due to the rough, boggy terrain. It wasn’t until1673 when Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet, two French explorers who were assigned to tread tough the then French-owned land, came through the marsh on their way back to the French-Canadian territory. Seeing potential in the land as a place to spread Christianity to the local tribes, Marquette stayed behind and built a house on the land.

Chicago was surrounded by plentiful prairies that were right for farmers to live off of at the time. Corn was a major crop but it was wheat that was more revered, but risky to harvest. Wheat could be easily planted in fields, but when it came to harvesting, a decent amount would not be sowed due to the intensive labor that surrounded the process. This however changed due to Cyrus McCormick and his grain reaper.

Fig. 1. A picture depicting Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet as they tread a waterway.

While Marquette ended up dying in 1675, two years after he built his house, it wasn’t long that explorers from the east would end up in the area. Eventually, a small community would arise as well as a fort, Fort Dearborn, in 1803. While the small community and fort would fall due to Native Americans razing the area during the War of 1812, Chicago would get back on its feet and become stronger than ever. What lead Chicago to become a booming metropolis were innovations in the wheat, meat processing, lumber, and mail order industries.

A painting depicting the Fort Dearborn Massacre. 500 Potawatomi warriors sneaked their way over hills to surround Fort Dearborn. What followed later was a brutal onslaught that killed 148 settlers.

WHEAT

Fig. 3. An Advertisement promoting the farmland in Illinois.

Fig. 4. A picture Cyrus McCormick.

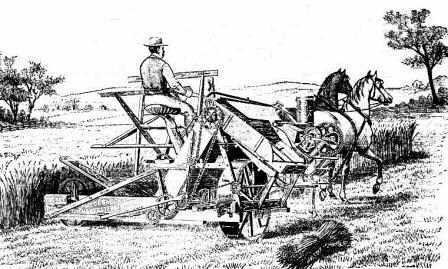

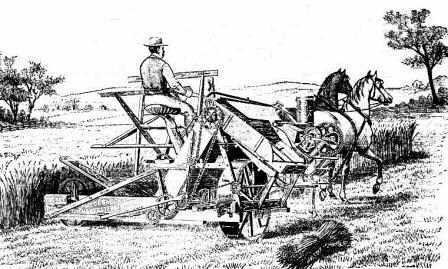

Born on February 15, 1809, Rockbridge County, Virginia, Cyrus did not originate the idea of a reaping machine. His father, Robert McCormick, had tried to invent a reaping machine that could be pulled by a horse that could be used to cut wheat in a quicker and effective way. While Robert failed in the sixteen years that he tried, Cyrus took up the mantle at age 22 in 1831. After a test run of using the newly-built reaper on a neighbor's field, Cyrus applied for a patent in 1834. After visiting Chicago in 1844, Cyrus saw the potential of his reaper would have on the grain harvesting. After making more improvements to the initial design in 1847, Cyrus headed westward and took residence in Chicago. To sell his reaper, Cyrus allowed farmers to pay a $30 deposit and pay the rest later when the grain harvest came and farmers had money; this was one of the first times that the idea of buying on credit was implanted with success. Around this time in 1848, mayor William Ogden took a risk to promote the growth of the city by creating a railroad line that connected to eastern cities and local towns; this railroad risked paid off in more ways than one because not only could the railroad move people, it could also move Cyrus's heavy reapers to the farmers who needed it the most.

Fig. 5. A Drawing of the McCormick reaper in action.

With the reaper selling strongly, farmers were able to bring in record amounts of grain. To store excess wheat, grain elevators were erected near train tracks and on the banks of the Illinois River to allow easy movement from storage to transportation. While the grain reaper was not invented in Chicago, the city was the first to use them extensively.

Fig. 6. A drawing of a grain elevator in Chicago around the 1850's.

Grain had a major part in influencing the economic market in Chicago. Due to the influx of grain and the quick transportation used to move, " the Chicago Board of Trade (CBOT), in full Board of Trade of the City of Chicago, was the first grain futures exchange in the United States, was organized in Chicago in 1848" (Chicago Board of Trade). Before the Board of Trade was established, farmers would sell their grain directly to a potential buyer. To take into account the massive influx of grain, the Board would have a farmer's grain graded; then "the grain of various farmers were then mixed together, the only distinction being the grain's grade" (Spinney 54). A potential buyer would then by the grain and pay a certain price depending on the grade. A farmer would then be given a grain receipt for which could be converted to money. This process allowed a streamlined economic system to be created and the grain market to become profitable. Grain was not the only part of agriculture to flourish in Chicago, as the meat industry grew as well.

MEAT

One of the first public projects in the city of Chicago, after it was established in 1833, was a public pig pen to store the wandering hogs that littered the streets eating trash. if a person wanted pork during these times, they would have to go to a local butcher; the butcher would then slaughter a pig and give the freshly cut meat to the customer. "Before the Civil War, Chicago possessed no 'meat industry.' Like most cites, its local meat needs were met by numerous competing stockyards" (Spinney 57). But when the Civil War broke out between the North and South, the demand for meat was high; because Chicago at this time was connected to other states by train and could easily deliver supply to soldiers, pork was seen as a profitable business venture. In 1864, the Chicago Pork Packer's Association was created to find a way to meet the demand for pork. A conclusion came from meetings the association had to solve the problem: that land would be purchased south of the Downtown area close to the train tracks to store, process, and ship meat with ease. This was the birth of the Union Stock Yards.

Fig. 7. The Union Stock Yards. It was called The Union Stock Yards because of the access that the yards had to the "union" of railroads.

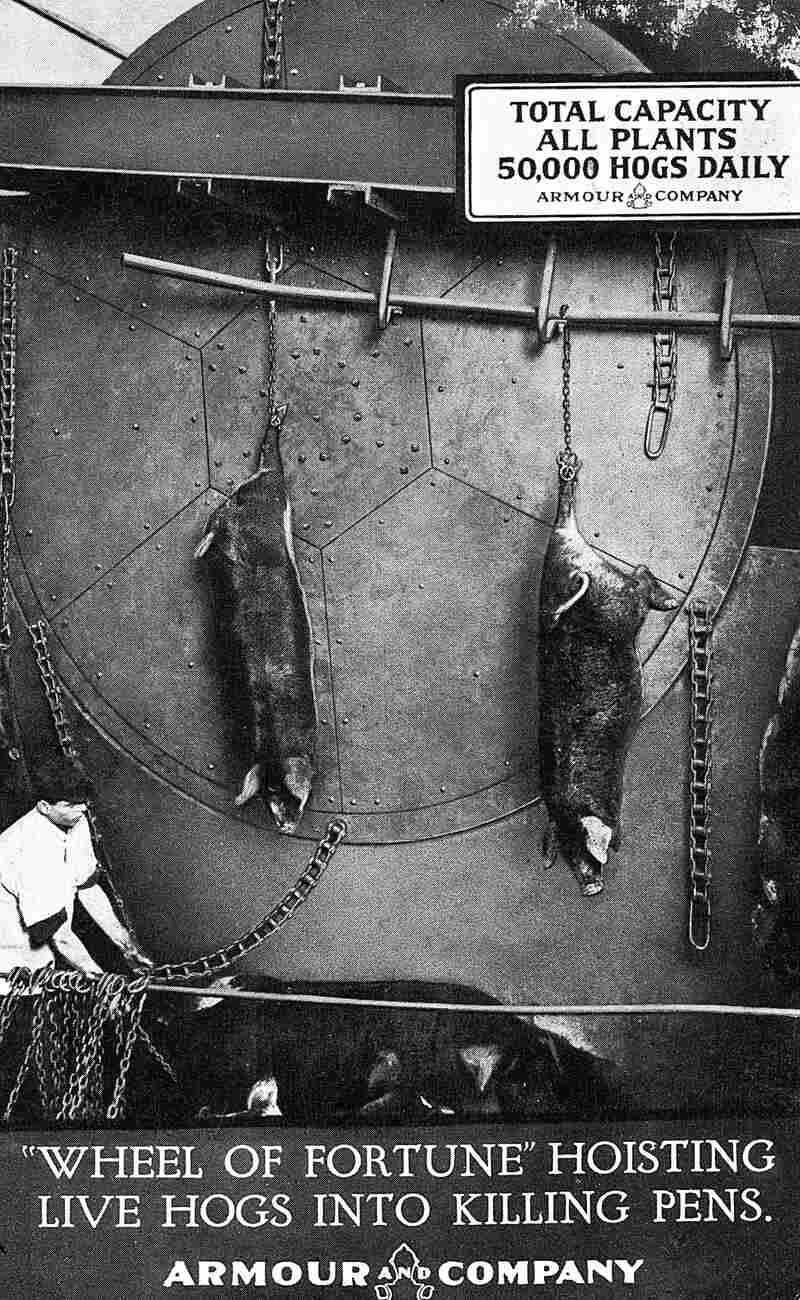

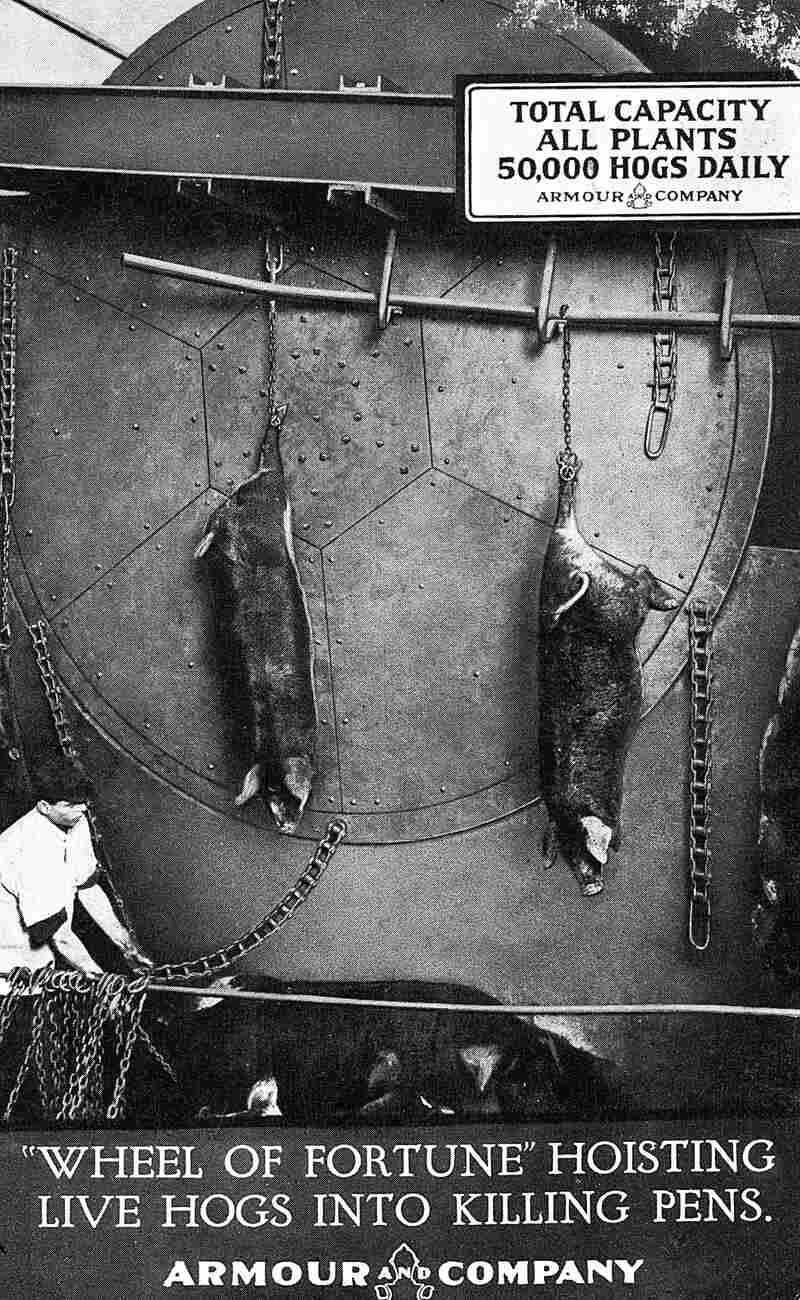

When the stockyards opened in 1865, it showed a sign of efficiency and innovation that was not seen at the time. To take care of the waste produced from the yards, around 30 yards of drainage pipes were installed to drain into the Chicago River; due to the decaying animal parts that were thrown out, a part of the River bubbles, known as Bubbly Creek, which still bubbles to this day. Inside the yards, a "disassembly line" was created to cut meat in an organized way. Strange components were made to keep the disassembly line working, such as the hog wheel. The hog wheel would have a hog hang by its foot while the wheel turned. As the hog was lowered, a butcher would slit the hog's throat, killing it. The hog would then move down the line until it was nothing more than the inedibles, such as the bones and hoofs.

Fig. 8. An Ad for the Armor and Company depicting the hog wheel.

Because meat cannot stay fresh without being refrigerated, it was hard for the yards to sell to far-away cities like New York. That all changed in the 1870's when Gustavus F. Swift created the freezer train car that could store items at cold temperatures, thus slowing the decomposition of meats. This was a major risk, as some people were skeptical that meat from far away would be edible; to combat this way of thinking, the prices of Chicago meat was sold considerably lower than the local-raised. When it was shown that the refrigerator car was able to keep meat fresh, the price of Chicago meat rose to a competitive price, allowing Chicago to challenge other meat processors on a national scale.

Since lumber was abundant in Chicago, it was only natural that most of the buildings be made of wood; while it made the cost of building a house relatively cheap, the downside was that the house would stand a chance of being burnt down if a fire started. On October 8, 1871, a fire started in a barn of Mrs. Catherine O'Leary; this fire would spread throughout the whole city. No building was safe in from this inferno. The fire was able to cross the Chicago River due to the waste that was dumped by houses and businesses and destroy all buildings beside the Water Tower and Pump Station buildings due to being made of stone. After the fire had settled, Chicago got back on its feet and built a new, fire-proof city, similar to how a phoenix rises from the ashes. As Chicago emerged from the rumble and built new buildings to replace the old, new business arose as well, such as mail-order catalogs.

References

Agriculture, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/30.html.

“Chicago: City of the Century.” PBS, 2003.

“Chicago Fire of 1871.” History , www.history.com/topics/great-chicago-fire.

“Cyrus McCormick.” Cyrus McCormick: Inventor of the Mechanical Reaper, www.american-inventor.com/cyrus-mccormick.aspx.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Chicago Board of Trade.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 29 Sept. 2016, www.britannica.com/topic/Chicago-Board-of-Trade.

THE FORT DEARBORN MASSACRE, www.prairieghosts.com/dearborn.html.

Lumber, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/767.html.

Mail Order. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/779.html.

Railroads, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1039.html.

Spinney, Robert G. City of Big Shoulders: a History of Chicago. Northern Illinois University Press, 2000.

“Union Stock Yards.” Chicagology, chicagology.com/prefire/prefire084/.

“The Union Stockyards.” Stockyards, The Union - WTTW, interactive.wttw.com/a/chicago-stories-union-stockyards.

Wilson, Mitchell. “Cyrus McCormick.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 June 2017, www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-McCormick.

Images

Fig.1.

http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/changes/images/current/river/cur_ilriv_joliet_300.png

Fig. 2.

https://chicagology.com/wp-content/themes/revolution-20/chicagoimages2/fortdearbornsamuelpage.jpg

Fig. 3. http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/agriculture/images/human_settlement/illinoislands_rrposter.jpg

Fig.4.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-McCormick

Fig.5.

http://www.american-historama.org/images/mccormick-reaper-jpeg.jpg

Fig.6.

https://chicagology.com/wp-content/themes/revolution-20/chicagoimages/firstgrainelevator.jpg

Fig. 7.

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEglvbU4_Nc4lpoILAhVIUVehUm8PdB5gOQfJZbTyE7pTPmsPZXiLYUX_i_Uuz5WrLmWWPmlycd6rVEgAXnhT9isEehkzHJceNAWUbgNbOYUeP0DlVrevaJdx7H_dpALtJxh-xhBnB3dH3-W/s1600/21_65.jpg

Fig.8.

https://media.npr.org/assets/img/2015/12/03/chi-pacyga-fig01004_edited1-ddc168feecfe1693e5a750f7f21613f8ff231cf1-s800-c15.jpg

Fig .9.

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/3030.html

Fig 10.

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/fallback/Map29a.jpg

Fig.11

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTWbZ3K19Felr3LywRFks0_xgF0I8tKtdDilxq1_JwX5GkG14UmgJ2nYrsiIDipq5XxVHWTD8njGjAWfCeAYzLk3EFwNBgo88gXB5NEwWLb0vtH3FTf84VIVrjaPc7IT3A27CMMUPVB0A/s1600/montgomery+ward+catalog+1895.jpg

Lumber

Chicago, being a swap next to a prairie, had little wood to use for building houses and other necessities; however, its location next to Lake Michigan made it an ideal place for a lumber trading post. North of Chicago were the abundant forests of Michigan and Wisconsin that held the precious resource needed. Trade boats would stop at a port in Michigan or Wisconsin, stock up on wood, sail to Chicago, sell the lumber, pick up some raw materials that Chicago could offer like grain, and sail back to Michigan and Wisconsin. Waterways like the Chicago River and the Illinois Michigan Canal allowed lumber to be transported out of the city and into the more rural areas.

Fig. 9. An engraving of the Lumberworks on the bank of the Chicago River. This area allowed lumber to be loaded up and shipped down the Illinois Michigan Canal, giving the well-needed lumber to the farmers in Southern Illinois.

Since lumber was abundant in Chicago, it was only natural that most of the buildings be made of wood; while it made the cost of building a house relatively cheap, the downside was that the house would stand a chance of being burnt down if a fire started. On October 8, 1871, a fire started in a barn of Mrs. Catherine O'Leary; this fire would spread throughout the whole city. No building was safe in from this inferno. The fire was able to cross the Chicago River due to the waste that was dumped by houses and businesses and destroy all buildings beside the Water Tower and Pump Station buildings due to being made of stone. After the fire had settled, Chicago got back on its feet and built a new, fire-proof city, similar to how a phoenix rises from the ashes. As Chicago emerged from the rumble and built new buildings to replace the old, new business arose as well, such as mail-order catalogs.

Fig. 10. A map showing the spread of the Great Chicago Fire. It originally started in a high Irish-populated area and quickly headed north, destroying all of downtown.

MAIL ORDER

"Montgomery Ward & Co., the world's first giant mail-order enterprise, started in Chicago just after the fire of 1871" (Mail Order). This business was revolutionary at the time because it allowed farmers to buy directly from a supplier rather than buy from an importing merchant and pay a fee. Because Ward bought massive amounts of supplies at a cheap price, he could sell at a lower price than his competitors; this practice is known today as wholesale selling. There was suspicion, however, among the general population that Ward was a fraud due to the too-good-to-be-true prices; he reassured the public that he would refund any purchases that did not meet their standards, another industry first.

Fig. 11. An 1895 Catalogue for Montgomery Wards. One could buy everything from farming equipment to furniture within these pages.

To appeal and attract potential buyers, "Ward advertised by sending out a catalog, which started as a single page but expanded quickly, growing to 32 pages in 1874, 152 pages in 1876, and nearly 1,000 pages by 1897"(Mail Order). Ward's catalog allowed rural Americans to have some of the finer things in life that originally were reserved for the wealthy class, such as jewelry, furniture, cookware, and finer clothes, for a reasonable price. This, in a sense, allowed the standard of living to rise in rural communities. It goes to show that small innovations can have a bit impact on others.

Agriculture, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/30.html.

“Chicago: City of the Century.” PBS, 2003.

“Chicago Fire of 1871.” History , www.history.com/topics/great-chicago-fire.

“Cyrus McCormick.” Cyrus McCormick: Inventor of the Mechanical Reaper, www.american-inventor.com/cyrus-mccormick.aspx.

The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. “Chicago Board of Trade.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 29 Sept. 2016, www.britannica.com/topic/Chicago-Board-of-Trade.

THE FORT DEARBORN MASSACRE, www.prairieghosts.com/dearborn.html.

Lumber, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/767.html.

Mail Order. www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/779.html.

Railroads, www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1039.html.

Spinney, Robert G. City of Big Shoulders: a History of Chicago. Northern Illinois University Press, 2000.

“Union Stock Yards.” Chicagology, chicagology.com/prefire/prefire084/.

“The Union Stockyards.” Stockyards, The Union - WTTW, interactive.wttw.com/a/chicago-stories-union-stockyards.

Wilson, Mitchell. “Cyrus McCormick.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 8 June 2017, www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-McCormick.

Images

Fig.1.

http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/changes/images/current/river/cur_ilriv_joliet_300.png

Fig. 2.

https://chicagology.com/wp-content/themes/revolution-20/chicagoimages2/fortdearbornsamuelpage.jpg

Fig. 3. http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/agriculture/images/human_settlement/illinoislands_rrposter.jpg

Fig.4.

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Cyrus-McCormick

Fig.5.

http://www.american-historama.org/images/mccormick-reaper-jpeg.jpg

Fig.6.

https://chicagology.com/wp-content/themes/revolution-20/chicagoimages/firstgrainelevator.jpg

Fig. 7.

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEglvbU4_Nc4lpoILAhVIUVehUm8PdB5gOQfJZbTyE7pTPmsPZXiLYUX_i_Uuz5WrLmWWPmlycd6rVEgAXnhT9isEehkzHJceNAWUbgNbOYUeP0DlVrevaJdx7H_dpALtJxh-xhBnB3dH3-W/s1600/21_65.jpg

Fig.8.

https://media.npr.org/assets/img/2015/12/03/chi-pacyga-fig01004_edited1-ddc168feecfe1693e5a750f7f21613f8ff231cf1-s800-c15.jpg

Fig .9.

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/3030.html

Fig 10.

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/fallback/Map29a.jpg

Fig.11

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTWbZ3K19Felr3LywRFks0_xgF0I8tKtdDilxq1_JwX5GkG14UmgJ2nYrsiIDipq5XxVHWTD8njGjAWfCeAYzLk3EFwNBgo88gXB5NEwWLb0vtH3FTf84VIVrjaPc7IT3A27CMMUPVB0A/s1600/montgomery+ward+catalog+1895.jpg

Comments

Post a Comment